Photo by Rick Kane

By Jim Olson

Click here to read FLOW’s full proposal formally submitted today to the International Joint Commission calling for an emergency pilot study. Click here to read a summary.

The International Joint Commission (IJC) on July 24 hosted a two-hour public listening meeting in Traverse City in the West Bay Resort, located on the shore of West Grand Traverse Bay. After introductions came a performance drawing from a collage of “Love Letters to the Great Lakes” curated and read by celebrated local writer Anne-Marie Oomen and three others to the accompaniment of bassist Glenn Wolff and trombonist Steve Carey.

A standing-room only crowd in excess of 200 people—the largest on the IJC tour so far—voiced its concerns for threats to the Great Lakes: Enbridge Line 5, nuclear waste storage, invasive species, bottled water, plastics and privatization, and harmful algal blooms. But the most threatening concern, one that drives or is exacerbated by the others, was the elephant in the room: the unprecedented record high water levels, which are causing havoc throughout the Great Lakes region.

To get to the IJC listening session, I decided to walk from my office, a normally direct path along East Front Street to the steps leading down through the memorial to Dr. Jim Hall and his son Dr. Tom Hall’s memorial—fitting given their constant work and passion for water and conservation—to the walkway along the Boardman River and under Grandview Parkway. It’s typically a 5-minute jaunt to the resort. But on this day an orange warning sign stopped me: The river overflowed the walkway with more than six inches of water. So I backtracked and dodged the rush hour traffic on the Parkway to the opposite side, and made my way to the meeting.

Photo: The Boardman River washes over the boardwalk in downtown Traverse City in July 2019.

Historical water level records for the Great Lakes show a general span of around 30 years from a significant low-level to high-level period. This year’s swing to a record high-water level in June from a record low-water level in 2013 took only six years. This year’s precipitation in Traverse City is trending 10-percent above the average rainfall so far. Farm fields, homes, businesses, and coastal communities are flooded. Shorelines are gone or shrinking, while erosion, more sediments, and high-water levels have destroyed homes and public beaches or infrastructure. Recent reports on the climate change impacts in the Great Lakes Basin project a 30-percent increase in precipitation, or an increase of nine inches a year or a total of 43 to 44 inches annually in Traverse City. If the current record high 10-percent increase is already wreaking havoc, what will happen when the increase is tripled?

Climate Change already impacting the Great Lakes system

The startling hydrological effects of climate change already are causing significant impacts to the Great Lakes, tributaries, their shores, and communities. These effects and impacts only will worsen as the water balance and quality begin to change because of the changes in the hydrologic cycle and watersheds, threatening massive destruction of natural resources and human habitats. It will amount to billions, if not trillions, of dollars in damage—perhaps the closure of Chicago’s fabled lakeshore trail and other waterfronts, the closure of water-dependent nuclear power plants, wetlands-turned-lakes, floodplains-turned-wetlands, flooded farmlands useless for crops, overwhelmed public water and sewer infrastructure. The list goes on and on—shoreline property damage, loss of beaches for swimming, health threats from flooded sewage, failed stormwater and erosion infrastructure, damage to state park and other public harbor and shoreline facilities, and runoff from contaminated properties all flowing into the Great Lakes.

How will people, communities, businesses, and natural systems cope with these water flows, levels, and loss of coastline, property, infrastructures, and public and private uses? All I had to do to make the meeting was dodge through traffic on Grand View Parkway. No big deal, right? Will the affected interests simply accept the loss and adjust, paying the millions or billions to adapt infrastructure and facilities or private homes? Will the governments fund adaptation programs to move or redesign harbor and waterfront facilities and other infrastructure? Will governments here and across the world revisit the Paris Climate accord, and finally reduce greenhouse gases along with massive expenditures to adapt and become resilient, necessary because reduction of greenhouse gases will only mitigate not prevent the oncoming damage? According to the most recent October 2018 Report from the UN International Panel on Climate Change, nations, states, and people have only a decade to take every possible action to stem and reduce the inevitable effects and impacts of climate change.

Climate Change pushing legal and policy frameworks to the limit

In addition to the oncoming harm and untold damage, the legal and policy regimes that protect the Great Lakes, and which all of us in the Basin and beyond support, are threatened—pressed to their limits is more like it. These include the Boundary Waters Treaty that set up the IJC in 1909 to protect water levels and prevent pollution of the Great Lakes; the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement that safeguards ecosystems, water quality, health, and recreation; and the Great Lakes Compact and a parallel agreement among the Great Lakes states and the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

For example, the 1909 Treaty prohibits diversions out of four of the five Great Lakes that affect water levels without a rigorous review and approval by the IJC commissioners (Lake Michigan is not an international water even though, hydrologically, Lakes Huron and Michigan are one lake). We think of “diversions” as human-made transfers of water into or from a river or lake (sometimes groundwater) system from a dam, reversal of a river, a pipeline, or a drainage canal–such as the Chicago diversion out of Lake Michigan waters to the Mississippi River, or the Long Lac and Ogaki-Lake Nipigon diversions into Lake Superior that would otherwise flow to Hudson Bay, or Erie Canal out of Lake Erie across New York to the east coast. In each instance, the IJC, guided by water-level study boards, determines the effect on the levels of the Great Lakes to prevent adverse impacts to ecosystems, harbors, shipping, fisheries, public infrastructure, hydroelectric dams, recreation, and riparian public and private property.

But extreme changes in climate from the failure to reduce greenhouse gases now threaten to remove water into or out of the Basin far beyond what the IJC typically controls. Climate change or the Anthropocene was not on anyone’s mind when the Treaty was signed in 1909. The drought and record low levels 6 years ago diverted more water out of the lakes and this year’s increasing precipitation and record high levels are as much of a diversion affecting levels as a dam, canal, or pipeline. Unlike proposals to divert water on one side of the international boundary, these extreme weather events whipsaw the lakes and their ecosystems, causing serious ecological, infrastructure, property and economic damage on both sides of the border.

Climate Change is a diversion of water

For another example, the Great Lakes Compact bans human-made diversions of surface and groundwater outside the Great Lakes surface divide or boundary. The purpose of the ban is to protect the waters to assure a sustained quality of life and economy within the Basin. There are only a few narrow exceptions—diversions necessary for public water supplies in communities or counties that straddle the Basin with the requirement of treated return flow, emergency and humanitarian single-objective proposals, and the so-called “bottled-water loophole.” The Compact defines a diversion as a “withdrawal of water by human or mechanical means that is transferred from the waters in the Basin to a watershed outside of the Basin”—including the attempt of the Nova Group in 1999 to ship 156 million gallons of lake water a year in a tanker transport to China, the failed attempt several decades ago to divert water from Lake Michigan to the coal fields of Wyoming, or the oft-feared pipeline or diversion down the Mississippi River to save the Southwest or Ogallala Aquifer from overuse and drought.

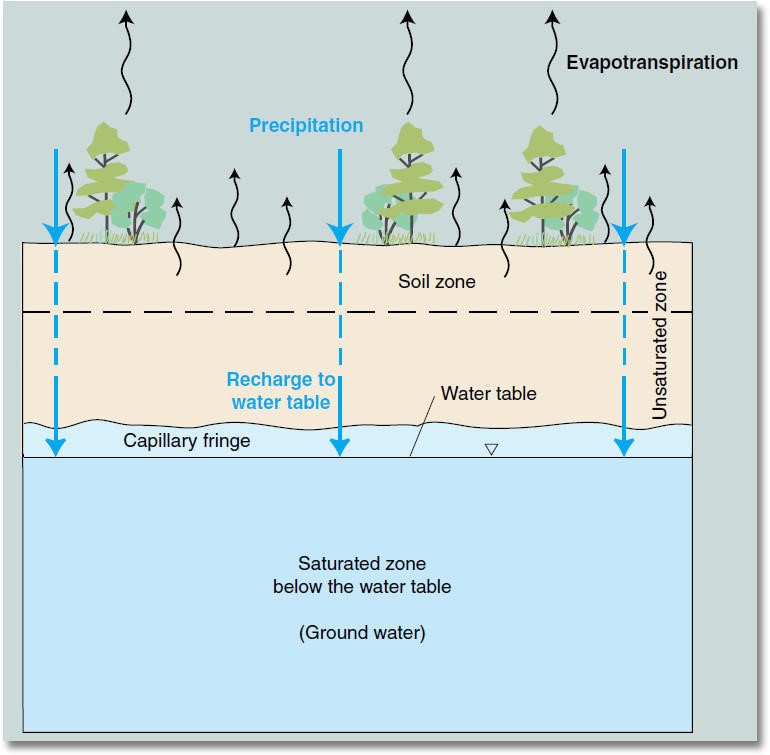

But what is the difference if human-made mechanical means or uses heat up the atmosphere, which increase evaporation and precipitation, affects the jet stream, and whiplashes areas of the planet between drought and deluge? If we look at the water cycle as a single hydrologic system, which it is, the Great Lakes are an arc of the whole water cycle. We live in a hydrosphere. What happens to one arc of the cycle affects the water levels in the other arcs. Climate change is as much a diversion of water into and out of the Great Lakes Basin as any other human conduct.

Fortunately, both the IJC in its charge to protect water levels and prevent pollution under the Treaty of 1909 and the Council of Great Lakes Governors and Regional Body (governors of eight Great Lakes states and premiers of the provinces of Ontario and Quebec) are aware of the effects and impacts of the climate crisis, and have at least advisory, quite possibly regulatory, authority to address the threats of climate change to the Great Lakes. It would be irresponsible and impossible for any of these governing boards to ignore the effects of climate change on water level or water quality decisions that affect the waters of the Great Lakes Basin in the future. The IJC already has issued a report and warning on the coming effects from extreme weather; sections of the Compact require that direct and cumulative effects from climate change be taken into account, including authority to modify interpretations and application of the principles and standards.

The ban and narrow restrictions on diversions are premised on the fact that the Great Lakes and tributary waters are essentially non-renewable; that is, based on the historic normal ranges of highs and low levels of the Great Lakes, there is really no water to spare for diversions elsewhere. While this may hold true for the normal range of flows and levels in the Basin and its watersheds, it will not hold true for unprecedented increases in flows and levels, such as the highs experienced this year. Strangely, there is suddenly too much water, and it is directly attributable to climate change. If the Compact is designed to keep water in the Basin from demands from regions experiencing drought or water scarcity outside the Basin, what happens when the effects and impacts of climate change push water levels above normal flows and levels and cause or threatens devastating ecological, economic, infrastructure, and public health impacts and losses? Should water be diverted or in-flows reduced or reversed on an emergency basis? If so, on what terms, when, and for how long?

In short, there is not only an ecological crisis, but also a law and policy crisis, and there is an urgent need for action.

The Boundary Water Treaty of 1909

The Boundary Water Treaty vests authority in the IJC to regulate and take other actions, such as reviewing actions that affect water levels and preparing and publishing references, reports, and guidelines to protect and manage Great Lakes water flows and levels (quantity) and pollution (quality); the Treaty prohibits any diversion “affecting the natural level or flow” of water unless authorized by both countries and through the IJC. The Treaty also specifically recognizes that our international boundary waters are a shared commons to be kept and managed for navigation, travel, fishing, hydropower, and other public and private uses and enjoyment for public and private purposes consistent with the principles of the Treaty and laws of both countries.

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1972, 1978, 1987, and 2012

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA) charges both countries—Canada and the United States—with a responsibility to protect the water quality of the Great Lakes from substances caused by human activity that adversely affect aquatic life; prevent debris, oil, scum and other substances that impair water quality and uses; and protect these waters and ecosystems against nuisance and toxic substances. The GLWQA also has established a protocol to address the existing and emerging effects from water flows and levels, including the significant increases in flows and levels from climate change. According to a former Senior Policy Advisor to the IJC, “this is critical because the IJC’s mandate is the only place where both water quantity and water quality come together in the Great Lakes Basin.”

The U.S. Common Law Public Trust Doctrine or Canada’s Right of Navigation and Fishing Doctrine

The legal regimes of both countries recognize a government obligation based on trust principles to protect navigation, boating, fishing, drinking water and sustenance, and related uses of the navigable waters within their countries and states or provinces. This trust protects these uses from interference or impairment, now and for future generations. The public trust doctrine provides a practical tool to evaluate and guide decision-making based on the existing and emerging effects from hydrogeological and land use watershed systems. The public trust standards that protect the waters and public and private uses from impairment provide the legal framework and process to embrace complex scientific evidence and to craft transboundary policy solutions that contemplate dynamic climate effects and various climate scenarios.

Over the past five years, the IJC has recognized and recommended implementation and application of the public trust doctrine as a framework or “backstop” set of principles to address the growing harms and threatened impact and impairment to the waters, ecosystem, and human use and enjoyment of the Great Lakes. These include the IJC’s 2014 Lake Erie report on Lake Erie algal blooms, the 2015 IJC 15-Year Review on Protection of the Great Lakes, and the 2017 Triennial Assessment of Progress under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. All three reports warn us of the “looming” threat to water quality, water resources, health, and quality of life in the Basin. And the Compact declares that the “waters of the Basin are precious public natural resources held in trust,” and are part of an “interconnected single hydrologic system.”

Click here to read FLOW’s full proposal formally submitted today to the International Joint Commission calling for an emergency pilot study. Click here to read a summary.

Jim Olson, President and Founder

Jim Olson is FLOW’s founder and president