Earlier this year, when it appeared that U.S. agencies would be unable to hire a full field staff to control sea lamprey in the 2025 season, the estimated economic damage was staggering. The feared staff reduction would have led to the survival of 2.5 million invasive lamprey, which would live to consume 12.5 million pounds of fish worth $264 million.

Fortunately, federal budget cutters backed off the staff reduction, which would have axed 12 probationary employees from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agency that carries out lamprey control on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes.

The continued menace of lamprey demonstrates not only the economic impact of non-native aquatic species, but also a fundamental attribute of these species: once they have entered the Great Lakes, they are usually here to stay, and require continued vigilance and control to protect the character of the Lakes. Governments spend over $25 million a year to keep lamprey from getting out of control.

The Great Lakes basin contains at least 188 documented aquatic nonindigenous species (ANS), making it one of the most heavily invaded aquatic systems in the world.

A new tool is helping researchers and program managers set priorities for protection of the biological integrity of the Great Lakes. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Michigan Sea Grant, and the University of Michigan have identified the top ten “aquatic nonindigenous species (ANS) determined to have the most significant negative environmental and socio-economic effect.”

The agencies employed a science-based method to determine the impacts of species. Criteria included their direct hazards or threats they pose to native species, alteration of predator/prey dynamics, aggressive competition with native species, and costly damage to human recreation, aesthetics, and economic activities.

Acting Director Dr. Jesse Feyen of NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory says the agency’s experts “have long studied the impacts of current and potential invaders in the Great Lakes. Our goal is to get the message out about the significant risks they pose.”

The ten least wanted:

Zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha). Native to Eurasia and introduced by ballast water discharge into the Great Lakes the zebra mussel causes displacement of native mollusk species, competition for food, and biofouling damage.

Quagga mussel (Dreissena bugensis). Native to areas in the Ukraine and the Ponto-Caspian Sea, quagga mussels also hitchhiked to the Great Lakes in ballast water. Like zebra mussels, quagga mussels decrease the abundance of zooplankton, reduce chlorophyll-a concentrations, increase water transparency, and accumulate pseudofeces, which can foul the environment). As the mussel waste decomposes, oxygen is consumed, pH is lowered, and toxic byproducts are produced. Biomagnification of organic pollutants can occur as pseudofeces is passed up the food chain.

Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus). The alewife, native to the Atlantic Ocean, entered the Great Lakes through canals. The species became widespread by 1960. Alewives became so abundant that they exceeded their carrying capacity in lakes Michigan, Huron, and Ontario, resulting in massive die-offs that littered shorelines and beaches. The invasion of alewife, coupled with destruction caused by the sea lamprey, led to the extirpation of lake trout from most areas of the Great Lakes.

Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). Parasitic fish native to the Atlantic Ocean, sea lampreys attach to fish with their suction cup mouth, then dig their teeth into flesh for grip. Sea lampreys feed on the fish’s body fluids by secreting an enzyme that prevents blood from clotting, similar to how a leech feeds off its host. Each individual lamprey is capable of killing up to 40 pounds (more than 20 kilograms) of fish over its 12-18 month feeding period.

Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum). An aggressive invader of forest lands throughout the eastern United States, stiltgrass can reduce the diversity of native species, reduce wildlife habitat, and disrupt important ecosystem functions. Stiltgrass is considered one of the most damaging invasive plant species in the United States.

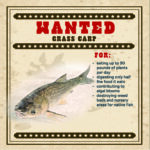

Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Grass carp feed on plants, consuming up to 90 pounds of food a day. The fish can only digest half of the food and expel the rest, contributing to algal blooms. Grass carp can destroy weed beds used by native fish for spawning and nursery areas and damage wetland ecosystems and waterfowl habitat.

Water chestnut (Trapa natans). Water chestnut is an aquatic invasive plant native to Eurasia and Africa. It was introduced in the United States in the mid-1800s as an ornamental plant. Water chestnut colonizes shallow areas of freshwater lakes and ponds and slow-moving streams and rivers and negatively impacts aquatic ecosystems and water recreation.

Common reed (Phragmites australis australis). The non-native strain of the common reed was accidentally introduced from Europe in the late 18th or early 19th century in ship ballast. The reeds form dense stands of stems that crowd out or shade native vegetation. Phragmites turns rich habitats into monocultures devoid of the diversity needed to support a thriving ecosystem. Non-native Phragmites can alter habitats by changing marsh hydrology; decreasing salinity in brackish wetlands; changing local topography; increasing fire potential; and outcompeting plants, both above and belowground.

Round goby (Neogobius melanostomus). Round gobies are freshwater fish that prefer brackish water conditions. They have voracious appetites and an aggressive nature which allows them to dominate over native species. Round gobies also have a competitive advantage over native species due to a well-developed sensory system that allows for enhanced water movement detection and the ability to feed in complete darkness.

White perch (Morone americana).These fish entered the lower Great Lakes in the early 1950s through the Hudson River-Erie barge canal system and spread westward. Spread by accidental inclusion in shipments for stocking inland lakes. They feed heavily on the eggs and young of important game species, and they have the potential to cause declines in native fish populations.

The most common shared negative effects were: direct hazards or threats posed to native species, alteration of predator/prey dynamics, aggressive competition with native species, and costly damage to human recreation, aesthetics, and economic activities.