Court Confirms Indiana’s 45-Mile Shoreline on Lake Michigan Owned and Held by State for Public Recreation Under Public Trust Doctrine

By Jim Olson[1]

Another state court confirms that the 3,200 miles of Great Lakes shoreline are owned by states in public trust for citizens to enjoy for walking, swimming, sunbathing and similar beach and water related activities on public trust lands below the Ordinary High Water Mark (“OHWM”).[2]

When Indiana was carved out of the Northwest Territories and joined the United States in 1816, the State took title in trust for all waters of Lake Michigan and all land below the OHWM along the state’s 45-mile shoreline.

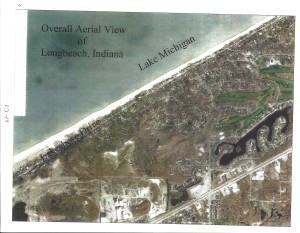

In 2012, the lakefront owners on Lake Michigan in Long Beach, Indiana, filed a lawsuit against the town of Long Beach, claiming they owned all of the land to the waters’ edge. Lakefront owners asked the trial court judge to prohibit any interference with their private property by town residents and the city who used the beach as public for walking, sunbathing, swimming, and picnicking since the town was incorporated. A group of local residents and homeowners organized into the Long Beach Community Alliance (“LBCA”), and intervened in the dispute to defend their public right of access for walking and recreation over the wide strip of white sugar sand between the shoreline and the retaining walls and yards of the lakefront owners. The Alliance for the Great Lakes (“AGA”) headquartered in nearby Chicago, and Save the Dunes (“STD”), a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting the dunes on Indiana’s shoreline, also intervened to protect the interests of their members who were citizens of Indiana and used and enjoyed the Lake Michigan shore.

In late December 2013, the trial judge ruled that the lakefront landowners could not interfere with the town or residents’ efforts to pass ordinances recognizing the land below the OHWM belonged to the state and was held in public trust for residents and citizens of Indiana.[3]

Not satisfied, the lakefront owners appealed to the Indiana Court of Appeals. In 2014, the appellate court recognized the trial judge’s ruling below, but remanded the matter back to the trial court for a more comprehensive decision on the State’s title and the public trust in the shoreline.[4] The court reasoned that the State of Indiana had not been made a party in the local suit, a prerequisite for a court ruling on a landownership and pubic trust shoreline dispute.

Another lakefront owner pressed forward with a related new lawsuit, again claiming ownership to the waters’ edge, based on their deeds that, they argued, gave them title to the waters’ edge, even if that meant their title cut off the rights of citizens of Indiana to the shoreline below the OHWM. This time the state was named a defendant, and the LBCA, AGA, and STD once more intervened.

It’s common knowledge that Lake Michigan water levels have fluctuated about 6 feet between highs and lows since the federal government started keeping records in 1860. In the late 1980s, the water levels and wave action threatened the lakefront owners’ retaining walls and homes. In 2013, the year the first court ruling came down, the water levels were so low, the distance from the waters’ edge to the lakefront owners’ retaining walls was wider than the length of a football field.

While the knowledge may not be so common for many citizens, the U.S. Supreme Court and the courts of states abutting the Great Lakes have routinely ruled that each state took title to the waters and lands of the Great Lakes up to the OHWM. In 1892, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that all of the Great Lakes’ waters and bottomlands to this ordinary high water mark are owned by the states in trust for all citizens.[5] The Illinois legislature deeded one square mile of Lake Michigan on Chicago’s waterfront to the Illinois Central Railroad company for an industrial complex. However, the Supreme Court voided the deed, and found that the public trust in these lands and waters is inviolate and could not be sold off, alienated, or even legislated away.

Despite this history, lakefront owners the Gundersons, pushed for exclusive ownership of the beach to exclude residents from the beach between their homes and the waters’ edge. The State of Indiana Department of Natural Resources, LBCA, AGA, and STD defended public ownership and the residents and citizens’ right to use the public trust shoreline for walking, swimming, sunbathing, and similar water-related recreational activities.

On July 24, 2015, LaPorte County Judge Richard Stalbrink wrote a near text-book-perfect decision on the public trust doctrine and ruled against the lakefront owners in favor of the state, LBCA, AGA, and STD, confirming that the beach below the ordinary high water mark to the waters’ edge belongs to the state and is subject to a paramount public trust that cannot be interfered with or impaired by lakefront owners.[6]

First, Judge Stalbrink followed the Supreme Court cases holding that the state obtained title to the waters and bottomlands to the OHWM when it joined the Union in 1816. Second, Stalbrink ruled that this beach land below the OHWM was held in trust for public walking, swimming, fishing access, and other public recreational uses. Third, the Court confirmed that Indiana’s definition of the OHWM was proper, given that the definition takes into account the physical characteristics that define a permanent shoreline as reasonable evidence of the public portion of the shoreline. Finally, Judge Stalbrink recognized that because water levels of Lake Michigan fluctuate, the width of the beach is subject to change, but that there is always a paramount right of the public to access the beach for proper public trust recreational activities.

As Judge Stalbrink observed near the end of his decision, ”Private lot owners cannot impair the public’s right to use the beach below the OHWM for these protected purposes. To hold otherwise would invite the creation of a bach landscape dotted with small, private, fenced and fortified compounds designed to deny the public from enjoying Indiana’s limited access to one of the greatest natural resources in this State.”[7]

(Author’s End Note: See rulings by the Michigan Supreme Court in 2005. Glass v Goeckel, 473 Mich 667, 703 N.W. 2d. 58 (2005), Ohio Supreme Court in Merrill v Ohio Department of Natural Resources, 130 Ohio St. 3d 30, (2011) (on remand before Court of Common Pleas, Lake County, Ohio for factual determination of OHWM); the Gunderson decision upholding public trust in Long Beach should control the decision in the companion case, LBLHA, LLC v Town of Long Beach et al., supra note 2, on remand to the Laporte County trial court).

[1]President and Founder, Flow for Love of Water.

[2]See Melissa Scanlan, Blue Print for a Great Lakes Trail, Vermont Law School Research Paper No. 14-14 (2014). (Professor Scanlan proposes walking trail within public trust lands and without interference with riparian use based on public trust doctrine in the Great Lakes); James Olson, All Aboard: Navigating the Course for Universal Adoption of the Public Trust Doctrine, 15 Vt. J. E. L. 135 (2014) (Author documents the application of the public trust doctrine in all eight Great Lakes states and two provinces of Canada).

[3]LBLHA, LLC v Town of Long Beach et al., Cause No. 46C01-1212-PL-1941. (The author, Jim Olson, discloses that he was one of the attorneys, along with Kate Redman, Olson, Bzdok & Howard, P.C., Traverse City, Michigan, in this case for the Long Beach Community Alliance in favor of public trust in shoreline).

[4]LBLHA, LLC v Town of Long Beach et al., 28 N.E. 3d. 1077 (2014). The Indiana Court of Appeals remanded to the trial court to add the State of Indiana as a party; this case will not proceed in same fashion as the Gunderson case discussed in this paper, which was decided by the same LaPorte County trial court.

[5]Illinois v Illinois Central Railroad, 146 US 387 (1892).

[6]Gunderson v State et al., LaPorte Superior Court 2, Cause No. 46D02-1404-PL-606, Decision, July 24, 2015, 22 pps. (Judge Stalbrink, Richard, Jr.); Indiana Law Blog, Ind. Decisions, July 28, 2015 http://indianalawblog.com/archives/2015’07/ind_decisions_m_709.html.; see also U.S. v Carstens, 982 F Supp 874, 878 (N.D. Ind. 2013).

[7]Id., Indiana Law Blog, at p. 3.