Oil & Water Don’t Mix: Potential Harm from Enbridge Pipelines in the Straits Stretches from Governor’s Mansion on Mackinac Island to Governor’s Desk

By Kelly Thayer, FLOW Contributor

September 9, 2014

It was a chilling portrait of a place accustomed to grandeur: Mackinac Island swallowed by a sea of oil. Passenger ferries and all other boat traffic halted to avoid igniting the spreading oil plume. Drinking water cut off indefinitely to prevent the island’s intake pipes in Lake Huron from sucking up the oil. The whitecaps under the Mackinac Bridge turned black.

There would be no visible cleanup activity by the state in the first hours or perhaps even the first days after the oil spilled, as response crews and equipment arrive from other regions of the country. A few weeks later, there’s the prospect of a million-gallon oil plume stretching for 85 miles – from Lake Michigan’s Beaver Island to Rogers City down the Lake Huron shore. A black stain on the Pure Michigan brand. An economic and environmental disaster at the Straits.

Those were just some of the sobering images that emerged during presentations Thursday (September 4) at Mackinac Island City Hall by the state’s chief oil cleanup official, a University of Michigan professor, and a team of legal and policy experts.

Despite a heavy downpour, approximately 75 people turned out to learn about the existence and implications of twin pipelines lying on the bottom of Straits of Mackinac, which carry nearly 23 million gallons of oil daily. Presenters detailed the threat the oil pipelines pose to the island and the Great Lakes, and how – in the view of a growing campaign of citizens and groups – the state is long overdue under law in conducting an open public process to evaluate whether the pipelines benefit the public and warrant repair, replacement, or removal. The informational event was sponsored by the Environmental and Natural Resources Board of Advisors of the Mackinac Island Community Foundation and other local civic leaders.

Response and Recovery Would Take Time

“A major event takes time to respond to,” as experts and equipment arrive from outside the Midwest, explained Bob Wagner, the state Department of Environmental Quality’s leader of oil spill cleanup. “You might not see us on the ground in the first hours. You might not see us on the ground on the first day.”

But recovery is possible in time, Mr. Wagner said, pointing to progress made so far in recovering more than 1 million gallons of heavy oil spilled in 2010 into about 40 miles of the Kalamazoo River near Marshall. The devastating oil spill was caused by pipeline company Enbridge, which also owns and operates the oil pipelines in the Straits about two miles west of the Mackinac Bridge.

Across its North American operations, Enbridge has spilled more than 7 million gallons of oil from its pipelines since 1999, at a rate of more than one spill a week, according to figures presented at the event by Liz Kirkwood, executive director of For Love of Water (FLOW), a Great Lakes legal and policy center based in Traverse City.

A Canadian Shortcut through the Straits

Built in 1953 during the Eisenhower administration, Canada-based Enbridge’s 30-inch diameter “Line 5” pipeline starts at a pipeline junction in Superior, Wisconsin, that receives oil from Canada and North Dakota. Line 5 travels through the Upper Peninsula, including Crystal Falls, where Enbridge’s pipeline leaked 220,000 gallons of oil in 1999 and sparked a multi-acre fire, Ms. Kirkwood said. In fact, since 1988, Enbridge has had 15 documented failures on Line 5, resulting in about 260,000 gallons of oil leaking from their pipeline – with several of those breaks happening near the Straits, according to information Ms. Kirkwood offered.

At the Straits, Line 5 splits into two 20-inch diameter oil pipelines (each a little larger around than a basketball hoop) that lie roughly 1,000 feet apart along a bottom reaching depths of 270 feet in powerful currents. The twin oil pipelines continue for about four miles before reaching the shore in Mackinaw City and recombining to be a single 30-inch pipeline again. Line 5 then traverses the Lower Peninsula and eventually crosses the St. Clair River near Port Huron and connects to other oil pipelines at Sarnia, Ontario.

Concern Turns to the Great Lakes

After Enbridge triggered the largest inland oil spill in American history in the Kalamazoo River, many residents, officials, and public-interest groups including FLOW turned their attention and concern to Enbridge’s pipelines in the Straits, an ecologically sensitive area linking Lake Michigan and Lake Huron with currents transporting volumes of water at more than 10 times greater than the flow over Niagara Falls.

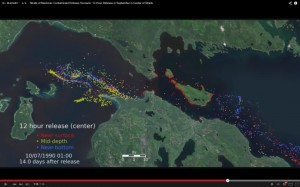

In response, the National Wildlife Federation commissioned a study in the spring of 2014 by the University of Michigan Water Center to use scientific computer modeling to create video animations depicting where a spill of a million gallons of oil – U of M’s “conservative” estimate of the amount of oil that resides in the pipelines in the Straits at any time – would spread over a 20-day period.

“The currents at the Straits are complex and multidirectional. The top of the water is not always moving and behaving like the middle or the bottom,” said University of Michigan Prof. Knute Nadelhoffer, director of the U of M Biological Station, as he played several of the oil spill videos that were developed by his university colleagues.

The Mackinac Island audience watched with rapt attention as an animation showed that a pipeline oil spill in the Straits would slosh back and forth with the currents and contaminate broad portions of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron and its shoreline communities, fish, and wildlife. The shores of Mackinac Island and St. Ignace were awash in oil, their residents and businesses cut off from the source of their drinking water – Lake Huron.

Depicting disaster at the Straits: A still from a University of Michigan animation showing the projected extent of a million-gallon oil spill at the Straits two weeks after the simulated 12-hour release. Mackinac and Bois Blanc islands could be surround by surface oil (red dots), with some oil at mid-depth (yellow dots) heading west toward Beaver Island and some near-bottom oil (blue dots) stretching east toward Rogers City.

A Growing Call for State Action

To avoid such a calamity, a host of environmental groups – including FLOW, the Michigan Land Use Institute, the Michigan Environmental Council, the Environmental Law & Policy Center, the Sierra Club, and TC350 – are working to raise public awareness about the pipelines in the Straits through events, publications, television ads, and a website (www.OilandWaterDontMix.org). The organizations are seeking citizen support for their petition calling on Gov. Rick Snyder to take charge and enforce state law and a state easement requiring Enbridge to:

- Share information about the contents and condition of the pipelines in the Straits,

- Comply with all terms and conditions of the existing easement, and

- Immediately apply under the Great Lakes Submerged Lands Act (GLSLA) for permission for its pipelines to occupy state-owned Straits bottomlands. The state law requires an open public process to evaluate the threat posed by the pipelines and determine what actions should be taken to protect the Great Lakes from a catastrophic oil spill.

“The time for the state to act is now,” Liz Kirkwood, FLOW executive director, told the Mackinac Island City Hall crowd, citing Enbridge’s spotty safety record, recent increase in the quantity of oil coursing through the Straits, and admission to violating the 1953 easement by not installing the required anchoring structures every 75 feet along the submerged pipelines. While it’s true that the federal government retains oversight over most oil pipeline issues, the state of Michigan has a unique and perpetual duty to protect the public’s interest in its Straits bottomlands and the water for drinking, boating, swimming, fishing, and hunting.

FLOW president Jim Olson explained that the state essentially is the landlord and cannot allow a private interest to occupy lands – in this case, private oil pipelines on state-owned Great Lakes bottomlands – held in “public trust” without finding there to be a public benefit and imposing and enforcing strict conditions. The state has never conducted an open public process under the GLSLA to evaluate the benefit to the public and the risk to the environment and economy, Mr. Olson said.

Deep Concern

After the last presentation, the first audience member to comment conveyed a level of concern about the Straits pipelines that was echoed by several others to follow: “It’s a disaster just waiting to happen out there,” a man remarked. In the event of an oil spill at the Straits, state and local officials explained that ferry service and the drinking water supply would be cut to Mackinac Island until the threat of fire and contamination recedes.

Another person asked about the life expectancy of the 61-year-old oil pipelines in the Straits, which Enbridge describes as indefinite, while another attendee wondered what circumstances might trigger an oil spill. Mr. Olson said that a state review of the pipelines under that GLSLA should answer those and many other safety questions.

“What about a spill in the winter?” someone asked, a reasonable query considering the Straits were frozen over into spring this year. “Everyone recognizes… winter is going to be a challenging time,” said Mr. Wagner, the DEQ cleanup chief, noting that Enbridge conducted a simulated oil spill response in the winter of 2011 and would conduct another drill this fall where Line 5 crosses the Indian River.

After the event, as people filtered out of city hall, back out onto car-free streets of pedestrians, bicycles, and horse-drawn carriages, the rain had lifted, but the mood had not. The state’s most idyllic setting, Mackinac Island offers yesteryear isolation from outside concerns and a summer residence to Michigan’s governor. But the very modern concern of an oil spill engulfing the island and its way of life had now reached its shores and its residents. And some were now looking to Lansing and the governor.

###

Thanks for the informative article. I’ve been alarmed about this issue since first learning about it several months ago. We need to sound the alarm and FORCE authorities to take action. As mentioned in the story, this IS a disaster waiting to happen.

I would be interested in participating in a march on Lansing to help generate awareness among the public and our state officials.

Instead of planning how to RESPOND to an oil spill, let’s work on PREVENTING one. And that starts with replacing this 61-year old pipeline NOW!

Steve much appreciate your comments above (9-12-14) Just reading Dec. 23, 2014

HOWEVER ~ I adamantly disagree with “replacing” I think we should rather STOP this from being allowed (GREED for some private corporation I’m sure!) Let Canada take care of building their own refineries to get their mined oil ready for export!!! Why should this EVER have started? !! REMOVE, REMOVE, REMOVE the oil from flowing.