As FLOW’s Communications Designer, I have been working in our Traverse City office since January, creating print and web content that gets the word out about FLOW’s policy programs that help protect the integrity of Great Lakes water with the vision of the commons. I have been given the great opportunity to work with our team on a number of tasks, from fundraising and grant writing, to research and policy reports, to event organizing. One experience remains with me as the most interesting to date (the one where I learned to embrace–or at least redefine–failure, something we all face from time to time): The Michigan Corps Social Entrepreneur Business Plan Challenge.

Serendipity and Facebook brought FLOW and Michigan Corps together. Back in April, a college friend working with Michigan Corps posted on Facebook about “The Challenge” – a business plan competition for social entrepreneurs with start-up or emerging companies. I clicked, I scrolled, and read the five-point checklist for a Great Social Entrepreneur:

- The entrepreneur is a tenacious leader with a pragmatic vision;

- The solution addresses a clear social problem;

- The solution changes systems, not just symptoms of the problem;

- The [business] model prioritizes social impact over financial gain;

- The model generates a sustainable funding stream.

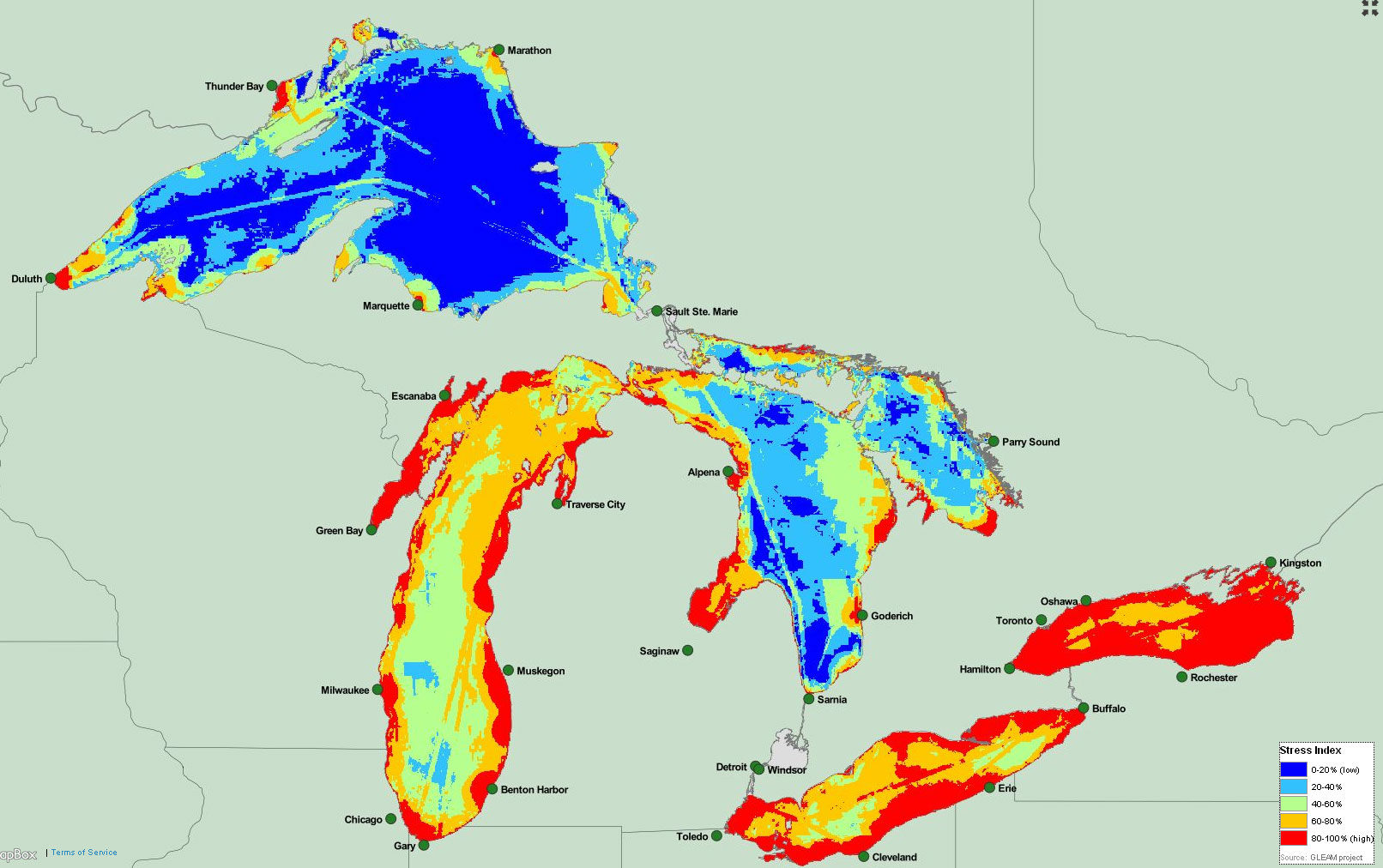

As I read over these points my face lit up and I was brimming with enthusiasm. FLOW would be the “ultimate” candidate for this competition! We have Jim Olson as our leader, and many who know Jim call him their “hero” as a water law champion. His vision is to work proactively to improve policy that protects water, rather than defend against or fight over discrepancies of inadequate law. Our solution to improve Great Lakes water policy directly addresses the social (and environmental) impacts of the threats harming the Great Lakes (see map – red is bad).

The solution of starting from the core value that water is common to all and held in the the public trust, which we at FLOW take to heart and specialize in, fundamentally addresses the whole system or framework–the policy. We work on policy because it ultimately determines the way in which we view, protect, and impose limitations on how we can use (or abuse) our water. FLOW programs seek to help communities and governments to improve their policies, and as a non-profit we do much of our policy and consultation work at pro-rated and discounted rates. We’re not in this to make a profit, but to cover our costs and make a difference–this is our “profit.” And with our awesome Great Lakes Society member supporters–that unique group of people and businesses who understand and are dedicated to our mission to save the Great Lakes with sound policy and strong commitment–we’ve got a growing stream of donations that will help us to get our work done.

The Challenge

So we at FLOW threw our hat in the ring and submitted our business plan to “The Challenge” in May. By June, the Michigan Corps folks read all the 160 business plan entries, and selected FLOW as one of the top 12 participants! While we didn’t win the big bucks, we received really valuable feedback from the judges who had clearly been intrigued with our nonprofit business plan and wanted to help us succeed. FLOW Communications Director Eric Olson and I went down to Lansing and attended the award ceremony, which dovetailed with the Michigan Economic Development Corporation’s Great Lakes Entrepreneur’s Quest award ceremony.

The “Ask the Investors” panel at the Michigan Corps Social Entrepreneur Business Plan Challenge award ceremony. June, 2013.

We met so many inspiring entrepreneurs whose missions were to create social wealth through a variety of unique business models. I’ll never forget squirming at the sight of blood when Gillian Henker of DIIME showed us pictures of her patent life-saving medical device invention, or cracking up at the subtle humor of Rich Daniels, whose mission to hire veterans into his FunPak company touched my heart. Even though we didn’t win, as Eric and I drove back north at dusk, we agreed that participating in the Challenge was a valuable exercise for FLOW. We met so many people and learned about so many great ideas. We learned about the many ways to run a nonprofit in an era of tight competition for funding, and we felt good about being selected as a finalist.

The Pitch

However, that’s not the story of “failure” I’m talking about, and FLOW’s relationship with Michigan Corps didn’t end there in Lansing. As runners-up in “The Challenge” we were given the opportunity to join in a three-month fellowship, hosted by Michigan Corps, with coaching from the awe-inspiring business strategist and consultant for The Public Squared, Richard Tafel. Our Executive Director Liz Kirkwood did the majority of the training sessions, and I jumped in at the end to help her with our “final project” (which gave me flashbacks of college deadlines, and was just as nerve-wracking). The October capstone of the fellowship was the opportunity to give a five-minute pitch to a panel of high-level investors looking to invest in social entrepreneurs. This was a real world litmus test for all the work and strategizing we’d been up to. We were competing against other impressive social entrepreneurs and asking high-level investors to invest in us as a nonprofit where the returns would be purely social, rather than financial. Not an easy task!

For our pitch, we decided to speak in a language that investors get – money. Using the bank trust analogy, we explained how our “special sauce” was our public trust policy strategy for water and the Great Lakes. If the “asset” is the Great Lakes water, then the governments are the “trustees” who are required to protect the asset for the “beneficiaries” – you, me, and all the 40 million residents in the basin. Is government doing a good job? Are they accountable? Is our trust safe and improving?

Here we are with the entire Michigan Corps Social Entrepreneur Fellow cohort and our consultants, mentors, advisors, and new friends.

At the pitch summit in Detroit, the morning workshop was a lesson in “design thinking” from Mike Brennan of United Way for Southeast Michigan. We learned a lot through his Venn diagrams and four-quadrant modules, but the best lesson was about failing. His advice: instead of bending over backwards trying to insist that you have “the solution” to the problem you’re trying to solve, make sure that you’re using both research and observation to inform a prototype first. And then: fail. A lot. It wasn’t the first time we’d heard this at FLOW, a son-in-law of a Board member here told us to “fail forward.” Nonetheless, easier said than done.

One of the investors on the panel, Romy Gingras Kochran of Gingras Global, highlighted the importance of failing early and often, and she even suggested hosting a “failure conference,” where entrepreneurs tell their “I failed” stories. So the more I thought about this idea of embracing failure as a learning tool, the more I realized that FLOW needs to share a “failure story” from our past to help illustrate WHY we are a policy and education center, and not an advocacy and lobby group, or a defense fund, why we offer something that is both visionary and real in the field of water commons, the water-food-energy-climate change nexus, and public trust policy. It’s because we have failed before, and it launched us forward to where we are today.

#Winning…

In 2009, the volunteers and policy advisors of the (at that time) “FLOW Coalition” worked with then-U.S. Representative Bart Stupak (D-MI) to draft important federal legislation that would make a big difference for protecting the Great Lakes from the threat of water exports. Put this in the context of the 21st Century water crisis, and you see why it’s important to keep our water IN the Great Lakes ecosystem. The bill, which was about to report out of committee and be introduced on the floor of the House of Representatives, was to close a loophole that allowed for water to be exported from the Great Lakes provided that it was labeled an “end user product.” (This arguably means water as an “export,” which in the trenches of international trade law could weaken the defense of the Great Lakes.) It took a huge amount of effort and countless hours spent building a public campaign to support the legislation, working with other organizations like Food & Water Watch in Washington, DC.

The FLOW Coalition also worked on legislation at the state level in Michigan that proposed to extend public trust protections from surface water (lakes, rivers, streams) to also include groundwater (like aquifers). Why? Because whatever happens to tributary groundwater will impact the surface waters and wetlands they replenish. Protecting water at every step in the hydrological cycle is important and a primary policy objective for FLOW. This legislation was important, and the idea is still important, because it helps protect water on a larger scale in the Great Lakes region, and it protects the water for all of us, public and private users alike.

FLOW #FAIL

Some say that the bills were poised for success, but they did not live long enough for any to ever truly know their viability. Why? Because the Affordable Health Care Act was introduced shortly thereafter, usurping the attention and impetus behind the FLOW legislative effort. Then we lost our political allies in the mid-term elections. When legislators pulled back from supporting these bills, FLOW was, at this point, tapped out. Our two-year flagship effort as an advocacy coalition for guarding the Great Lakes and our groundwater and surface water from export and abuse was over. It was a big, fat, #FAIL.

While we all could still benefit from federal and state laws better protecting our water with the public trust, FLOW founders and staff pulled back, knowing that it was time to re-evaluate our strategy for just how we could get this–and other important policy–accomplished in the most efficient, effective manner. From a coalition with a pinpointed goal, we realized that we had a big idea: enshrining water as a commons, public trust in our policy can protect citizen beneficiaries, communities, business, and quality of life for the whole region. These are ancient and core values, and we knew not to give up. We knew that our big idea was right, that we were addressing the important problem, but that our prototype was in need of refinement.

Our #FAIL demonstrated to us that it was worth the shot to try, and we almost succeeded, but events like the economic collapse in 2009 and the health care agenda took all of Congress’ attention in 2010. The lesson was that narrow windows of opportunity are not guaranteed. Going it alone for a single attempt with a federal legislative campaign means going back to square one, when things out of your control force you to scrap your efforts.

Resurget Cineribus

We realized after the legislative efforts were swept away in the health care debate, that the vision to save the Great Lakes from the many threats of this century requires education, deep education, as deep as the lakes themselves, so that the winds and whimsies of politics do not affect the goal and changes that are needed. Water is deep in all of us, we’re made of water, and literally it is our lifeblood. So is it for the Great Lakes and around the world. If people begin to connect, through education, that water is at the core of their lives and well-being, then they will support, vote for, and take action to save the Great Lakes when it is needed.

We also realized that there were more, equally important, low-hanging fruit on the policy tree that could be addressed as part of demonstrating and applying the public trust to protect Great Lakes water. What’s more, part of our failure was embedded in a lack of public awareness and education. The reason the public campaign took so much energy out of us is that we didn’t have a strategy building up to the campaign. Did anyone really know about the public trust? And that people, as legal beneficiaries of the Great Lakes water, can use the public trust to enforce an “umbrella” standard of protections for the water? Or did they know why groundwater needs to be protected by the public trust? Or did they even know enough to make the connection that groundwater becomes streams, rivers, and the Great Lakes, and that all are one? That if groundwater and surface waters are not protected by public trust, that they can more easily be abused or exported right out from underneath a farmer’s crops, a golf course’s aquifer, or a fly fisherman’s favorite river? After all, the public trust protects access, use, quantity and quality of our Great Lakes for fishing, boating, swimming, sustenance, navigation, the basics of life and community. If these are compromised, interfered with, or harmed, then citizens, knowing these rights and uses are protected, and can speak out and take action to prevent and restore the harm from these threats.

With so many questions to ponder, and so many gaps in knowledge to fill, the FLOW Coalition evaluated the need for education, and this is how FLOW became the FLOW policy and education center for the Great Lakes. Rather than only focus on export loopholes and groundwater protections, we recalibrated our mission and thus our operations. To solve a big, systemic problem like preserving the Great Lakes, we needed to pursue the big, holistic solutions. It was 2011 when FLOW began to beat the drum of public trust policy and education.

In this way, the FLOW Coalition was an important first step – a prototype for the steps to follow. When we went back to the drawing board, we came up with a two-pronged strategy for our next prototype: deep legal research and policy development on one hand, and education and training for both leaders and citizens on the other hand. We went through a phase where we were the FLOW Coalition, which undertook the education, and the Public Trust Policy Center, which performed the research and reporting. However, one hand didn’t know what the other was doing, and we saw that the interdependence of policy and education work was too strong to keep them separate.

So, we’ve moved past the bicameral organization prototype, too. Our objectives remain twofold: to educate and train leaders and citizens, and to undertake deep legal research and policy. Now, from an organizational standpoint, we are simply FLOW, the public trust policy and education center. Our programs vary and are topic-based, weaving both policy and education into the components of the programs. We have a much deeper and more insightful strategy for targeting our actions to our audience. So far, these programs have been successful. And now, with many thanks to our partners at Michigan Corps, we are prepared to move them forward, and are equipped with the tools for embracing the opportunity of failure. We learn from our #FAILs and improve ourselves to create more success in the long run. Even more importantly, like singing in public, we have learned to work boldly and steer clear of the shadows of reticence and into the lightness of sanguinity.